1945 Lockheed P-38L Lightning - N3800L

Built in 1945, this P-38 saw action as a fighter in World War II and later served as a civilian mapping platform. It came off Lockheed’s assembly line in June of 1945 as a P-38L-5-LO, serial number 44-53087, and cost $15,000. It saw brief action as a fighter and was then converted to a night fighter, but was never used in that role. When the war ended in August 1945, this airplane was sent for disposal to the U.S. Army Air Forces boneyard at Kingman, Arizona. When the government offered several of its surplus aircraft for sale in early 1946, the airplane was one of 48 Lightnings sold to a single buyer for $1,250 each. Most of these P-38s were “parted out” at great profit. Number 44-53087 remained intact and passed through three private owners before being sold to a Canadian mapping and survey company in 1951. It received a bubble nose and was used for aerial cartography. It continued in that role with several owners until 1961 when it was purchased by a member of the Confederate Air Force based in Texas, becoming the CAF’s first P-38. CAF acquired another P-38 in 1963 and, once again, 44-53087 was sold to work as an aerial mapping and survey airplane.

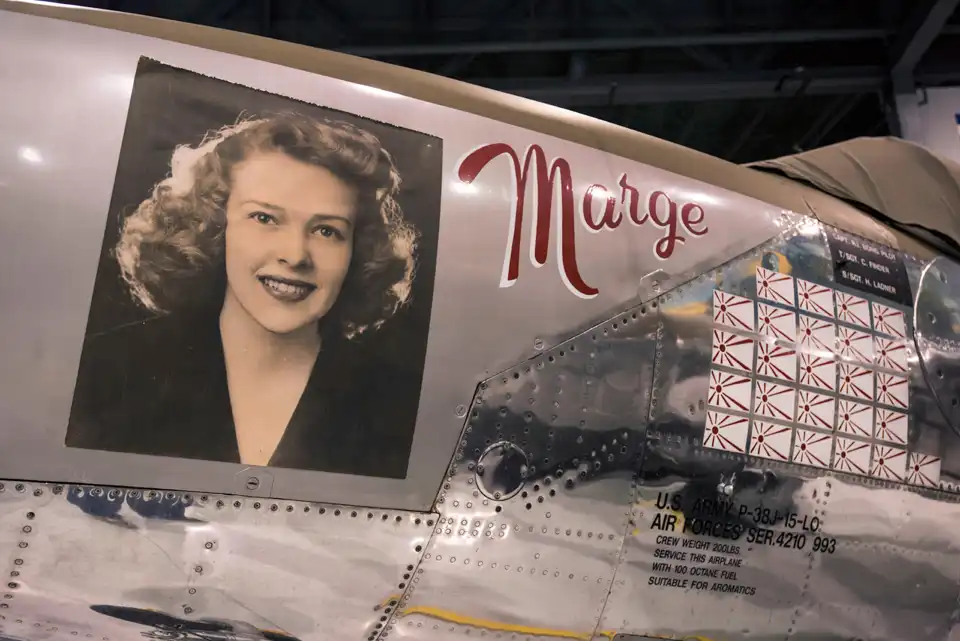

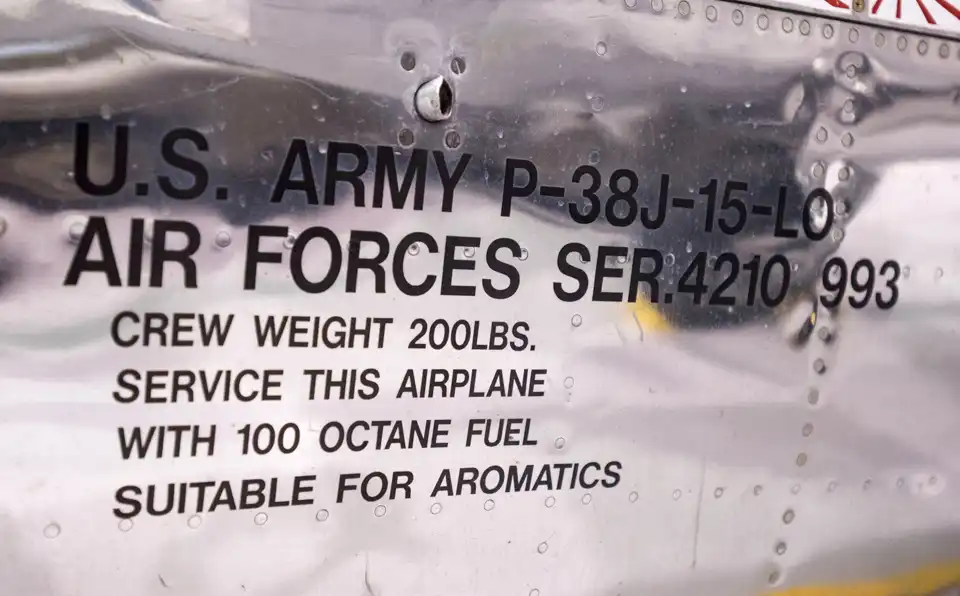

Sometime around 1970, another in the long succession of owners converted 44-53087 back to fighter configuration, with a fighter nose purchased from MGM movie studios. Finally, in 1981, the last private owners, Wilson “Connie” Edwards and Will Edwards Jr., donated the airplane to the EAA AirVenture Museum in memory of Connie’s brother, Bill Edwards. Restoration by EAA staff and volunteers took several years. The airplane was painted in the accurate markings of one of Maj. Richard Bong’s P-38s, a J-model – named Marge for his fiancee – and installed in the EAA AirVenture Museum’s Eagle Hangar, dedicated to the men and women of WWII aviation.

It is widely agreed that the three best American Army Air Forces fighter airplanes of WWII were the North American P-51 Mustang, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Of these three, the P-38 was the first to be deployed, the first to make a kill in aerial combat, the most advanced and versatile design, and the only one to be in continuous production throughout WWII. America’s two top WWII aces – Bong (40 kills) and Maj. Thomas McGuire (38 kills) – both flew P-38s.

The Lightning was successfully deployed in every theater of combat and in a wide variety of roles. It was especially effective in the Pacific Theater, where its exceptional range and the security of two engines allowed long-range combat missions over large expanses of water. P-38 variants were used as pursuit fighters, bomber escorts, ground-attack fighters, radar-equipped night fighters, light bombers, and target-marking pathfinders. The Lightning could carry a two-ton bomb load – as much as some medium bombers – drop its bombs, and immediately convert to a ground attack role. P-38s were even modified to carry two one-ton torpedoes, but that variant never saw action.

One of the most common variants was the F4/F5 unarmed photoreconnaissance aircraft, which carried up to five cameras in its nose. Nearly 1,000 P-38s were built or converted as photo recon aircraft during the war. By some accounts, P-38 photo missions brought back 80 to 90 percent of all aerial recon photos from that period.

Pluses & Minuses

The P-38’s unique design offered some advantages and disadvantages over the P-51, P-47, and other frontline fighters of the day. While the P-38 was considered no more difficult to fly than most single-engine high-performance fighters, pilots said it took about twice as much flight time to master the P-38’s full potential. It had excellent stall behavior when it was clean, but stalls became violent and dangerous when underwing stores (bombs, rockets, smoke canisters, or drop tanks) were added.

High-speed dives created turbulence and reduced elevator effectiveness, making it difficult or impossible to pull out of the dive – a phenomenon later understood as compressibility – the turbulence that builds up on a wing just before an airplane reaches the speed of sound. Lockheed engineers solved the problem with dive flaps that slowed the P-38’s dive and reduced the turbulence. Eight-degree “maneuvering flaps” could also be deployed at 250 mph or below, to slow the aircraft and tighten combat turns.

The cockpit was roomy and high. The “greenhouse” started at just above waist height on the pilot. That should have created exceptional visibility, but the engine nacelles and complex cockpit bracing created significant blind spots. The high seat position also meant less protective armor for the pilot. The tricycle gear gave good over-the-nose visibility and made the airplane much easier to land and taxi than many of its single-engine counterparts.

When it first entered combat, the P-38 could fly missions of four to five hours’ duration – a 500 to 1,000-mile combat radius, with 45 minutes over the target. Working for the Army Air Forces in the Pacific Theater, Charles Lindbergh developed “cruise control” techniques that extended the P-38’s endurance to missions of seven to eight hours.

The fire from wing-mounted guns in single-engine fighters typically converged at about 300 yards. The P-38’s four .50-caliber machine guns and one 20mm cannon were mounted on the fuselage centerline, permitting aerial kills and strafing runs at ranges of up to 1,000 yards, and the P-38’s guns and cannon could destroy any aircraft, most locomotives, and some small ships.

Aircraft Make & Model: Lockheed P-38L Lightning

Length: 37 feet, 10 inches

Wingspan: 52 feet

Height: 12 feet, 10 inches

Empty Weight: 12,800 pounds

Max Takeoff Weight: 21,600 pounds

Seats: 1

Powerplants: Two Allison V-1710-89/91 12-cylinder, supercharged, counter-rotating engines

Horsepower: 1,475 hp

Cruise Speed: 290 mph

Maximum Speed: 414 mph

Combat Range: 450 miles

Armament: Four .50 caliber machine guns, one 20mm cannon, up to 4,000 pounds of rockets, bombs, or depth charges